The issue of women’s empowerment continues to be of paramount significance in determining the future of the incomplete Arab revolutions. Numerous scholars, activists, and feminists have commented with concern about the precarious position of women after the contagious revolutions, which started in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. Many have expressed anxiety that the controversial gender issue in the Middle East will dominate the coming years, as even Christian leaders transmit Islamists’ pressure on women to dress “more modestly” to their communities. Others have remarked that misogynist attitudes are observable today across the post-revolutionary Arab states, because the Islamists in power have revealed themselves to be agents of an “Islamic neoliberal” ideology that works hand in hand with constraining measures regarding women. These observers have pointed to various shocking acts that all converge in one direction: the targeting of women’s bodies.

The aged President Hosni Mubarak had long embodied the oppressive and institutionalized patriarchy in Egypt. After Mubarak’s ouster in February 2011, an ageing military junta replaced him, and continued to use violence to subdue protest. It was as if a targeted vengeance were being directed against Egypt’s youth, and as if the generational conflict between the old generals and the young protesters had to be played out through the mutilation of young bodies.

Today, almost a year since the election of longtime Muslim Brotherhood figure President Mohamed Morsi, there is a general feeling that nothing has really changed in terms of citizens’ rights. None of the security officials responsible for the series of killings of protesters since January 2011 have been convicted. As this in turn sparks new demonstrations, the Brotherhood regime continues the use of thuggery and public violence, together with sexual harassment, to terrorize citizens and deter them from protest in Tahrir Square.

But these policies, and the statements legitimizing them by military officials and Islamist politicians alike, have become the butt of jokes and biting comments in oppositional media. Among the most striking examples of this has been the graffiti art of young Egyptian activists across the country. The impertinence in their depictions of the authorities has become one of the most powerful ways of unmaking the system. Indeed, many believe that the military junta had been defeated morally well before Morsi replaced it, thanks to the public ridicule of its violence in popular jokes and graffiti.

.png)

[“I want to kiss you”, graffiti outside the al-Ahly Club in Zamalek, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 12 September 2012)]

Public Violence against Women’s Bodies: Egypt under SCAF Rule

Once the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) took power in February 2011, sexual harassment became an obvious means of intimidating and publicly humiliating protesting and dissenting women. Sexual assault was used to deter foreign female journalists, as well as to tarnish the morally pristine image of Tahrir Square, which had been a famously harassment-free zone throughout its occupation in January and February 2011.

In March 2011, so-called “virginity tests” were undertaken on female protesters by military personnel. The army spokesmen justified this act by stating that it prevented them from being blamed for having “deflowered” young women protesters. One of the victims, Samira Ibrahim, filed a case against the army medic responsible. He was acquitted, like the majority of police officers implicated in the killings and injuries of thousands of protesters in January and February 2011.

.png)

[Samira Ibrahim, image on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 11 September 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: “Girls and Boys are Equal”, Figuring Iconic actress Suad Hosny graffiti on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 9 March 2012)]

The discourse of the former regime, which continued after February 2011, sought to equate protesting women with prostitutes, for having left their place in the home and headed out to demonstrations. By this logic, they deserved to be raped. Similar reasoning led some Salafist preachers and a pro-Mubarak television presenter to call a female protester – and victim of police violence – a prostitute, because she appeared scantily clad after her ordeal. When she went to join anti-SCAF demonstrations near the Egyptian cabinet building on 17 December 2011, the unknown female protester had been wearing her veil, and was dressed in jeans and a black cloak (abaya). The previous day, security forces had begun attacking protesters viciously, killing twelve, wounding hundreds, and dragging one body into a rubbish heap. That afternoon in Tahrir Square, several military policemen in riot gear violently dragged and beat up the veiled protester, leaving her blue bra exposed.

.png)

[Caption: “Blue Bra” graffiti, Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 16 March 2013)]

Ironically, the blue bra turned into a symbol of national contestation against both the SCAF and the Salafists. On 20 December 2011, activists organized one of the most significant women’s demonstrations against SCAF policies, marching from Tahrir to Talaat Harb Squares, and attracting thousands. As such women’s protests and marches against the military multiplied, the “blue bra” remained an iconic symbol. The protesters chanted for the end of military rule, and the slogan “Egyptian women are a red line” gained tremendous momentum. Soon, the city’s murals, and the cement walls, which the SCAF had erected after November’s protests in Mohamed Mahmoud Street, were filled with hundreds of blue bras.

.png)

[Caption: “Blue bra” assault, graffiti on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 28 September 2012)]

Just after the incident of the blue bra, painter Mohamed Abla produced a remarkable series of paintings, entitled Wolves, in which he drew the female protester being dragged by police forces with wolves’ heads. He exhibited the paintings in Abdin Square and marched, carrying them, through Tahrir Square with a group of artists. Abla’s act was disseminated via his facebook account, and protesters displayed photographs of his painting, similar to other graffiti on the blue bra, in public as a reminder that the incident would never be forgotten.

.png)

[Caption: SCAF erected wall in Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 21 February 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: 6 October Bridge, Zamalek, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 30 June 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: Graffiti painted during the Mohamed Mahmoud Street incidents of November 2012. The text conveys the message: “W for Women, We’ll Put Red Dresses on All of You”. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 23 November 2012)]

Protesting Women: Egypt under the Muslim Brotherhood

Today, under Islamist President Mohamed Morsi, violent attacks have continued to be a regime tactic for frightening female demonstrators. One victim was a female reporter who had been reporting clashes between Muslim Brotherhood members and opposition activists whom they prevented from entering Tahrir Square in October 2012. Late that night, a large horde of men attacked her.

Sexual assault then escalated to peak in December 2012. After Morsi’s unpopular constitutional declaration the previous month, young activists had set up a peaceful protest camp outside the presidential palace in Cairo. The Muslim Brotherhood sent armed supporters to attack the protesters on 5 December. The men set up their own torture chambers in collaboration with police, establishing a qualitatively new level of public violence. There followed what appeared to be the systematic gang raping of women protesters in Tahrir Square, by large numbers of thugs who moved in organized groups to isolate and encircle their targets. Such gang rapes have recurred with regularity since, as if sexual molestation were becoming a repertoire designed to smear the Square. Armed men had reportedly assaulted some twenty women in separate incidents over ten days in November 2012 alone – a tactic being used repeatedly by the regime to deter women demonstrators.

By February 2013, some members of the Islamist-dominated Shura Council were arguing that women who are victims of gang rape should be held accountable, as that they should not be demonstrating in Tahrir in the first place. This can only mean one thing: the regime is now legalizing crime.

.png)

[Caption: Graffiti by Mira Shehadeh, on SCAF wall in Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 1 March 2013)]

.png)

[Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 1 March 2013)]

The tactic of humiliation through sexual molestation of women, young and old alike has precedence in Egypt. The most common explanations are that such behavior is the indirect outcome of sexual frustration, or of taboos and inhibitions born of religious sanctions and segregation. Another reason often cited is the unbearable economic hardship associated with the increasingly consumerist and unaffordable institution of marriage, in a society with some eight million unmarried men and women above the age of thirty-five, while premarital sex is taboo.

To my mind, these clichéd explanations remain simplistic. When the omnipotent authoritarian state that claims to be the spokesperson for Islamic morality, and constitutional defender of Islamic sharia, turns out to be the main perpetrator of sexual violence in the public sphere, then why would the “citizens” not follow the same violent path?

.png)

[Caption: “No to Sexual Assault”, Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 11 September 2011)]

.png)

[Caption: “Whatever is or is not revealed, my body is free, it is not to be humiliated”, graffiti on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 11 September 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: Feminist graffiti on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 11September 2012)]

Black Wednesday, 25 May 2005, marks the date when protesting women were sexually harassed in public for the first time in Egypt’s modern history. These women had been demonstrating in front of the Journalists and Lawyers Syndicates against a constitutional amendment that would have guaranteed the succession of Mubarak’s son to the presidency. They suffered attacks by the paid thugs of the then ruling National Democratic Party. This incident was followed by a series of gang rapes all over the city of Cairo that targeted young women during the season of the religious festival in 2006, whether they were veiled or not.

.png)

[Caption: Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 2 November 2012)]

All the attacks on women since February 2011 have been nothing but a remake, a déjà vu, in which paid thugs of the previous regime reappear, while the army and police forces stand around as voyeurs, if not facilitators, responsible for this sexual harassment and countless other attacks on citizens.

.png)

[Caption: “Treat Me Like a Human Being”, graffiti on SCAF wall, Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 12 March 2013)]

Women in the Electoral Process and the Brotherhood in Parliament

The mesmerizing public visibility of women in Tahrir in January 2011 clashes powerfully with the near total invisibility of women in the parliament elected that November, and recently dissolved. Compared with Morocco and Tunisia, Egypt scores the lowest in women’s parliamentary representation, with only eight women having won in the elections, and two others appointed.[1] Among the reasons for this defeat, Hania Sholkamy cites a “state sponsored feminism” that imposed “an unpopular quota for women within corrupt electoral practices”.

.png)

[Caption: Painting by Alaa Awad. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 26 March 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: Painting by Hanna al-Degham. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 9 March 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: Na’ehat, mourning women, painting by Alaa Awad. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 21 February 2012)]

.png)

[Caption: Wassifat, ladies-in-waiting confronting the military, painting by Alaa Awad on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 12 March 2012)]

The theme of Egypt’s short-lived post-revolutionary parliament’s sessions, from January to June 2012, was the Islamists’ alarming obsession with exercising control over women’s bodies, through their reactionary draft laws on gender. These included bills encouraging female circumcision, demanding the marriage age for women to be lowered to nine years old, and rejecting the khul‘ law that allows women to file for divorce.

[Caption: “Don’t categorize me”. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 13 September 2012)]

One of the most vocal proponents of these measures was a woman herself: Freedom and Justice Party Member of Parliament Azza al-Garf, who has advocated the annulment of the anti-harassment law, citing her belief that it is women who are to be held responsible for such incidents, as their light dressing provokes such lustful acts from men. Garf alarmed Egyptian feminist groups by also calling for the abolition of the khul‘ divorce law, as well as the non-recognition of the offspring of illicit relationships, and the annulment of the recent law granting Egyptian nationality to the children of foreign fathers. Furthermore, Garf wanted to acknowledge the right of the husband to have sexual intercourse with his wife by force if she refused him, and to forbid women from traveling without their husbands (in order to enforce a requirement that they obtain their husbands’ permission to travel). She also wished to cancel the law stipulating that the first wife be informed about her husband’s second marriage, and to cancel the law that guarantees the divorced wife access to any housing which she acquired as private property.

Garf publicly supports “female circumcision”, or rather female genital mutilation – a practice that was banned in 2007 after years of feminist campaigning in Egypt. She calls it a form of “beautifying plastic surgery”. How then does she differ from the Salafists, who feel threatened by women in the public sphere, and advocate the banning of women from political life (which would expel Garf from parliament)? The Salafists’ demands include removing the age limit on marriage, legalizing marriage from puberty, and the stoning of the adulterers – all constituting a direct attack on women’s freedoms.

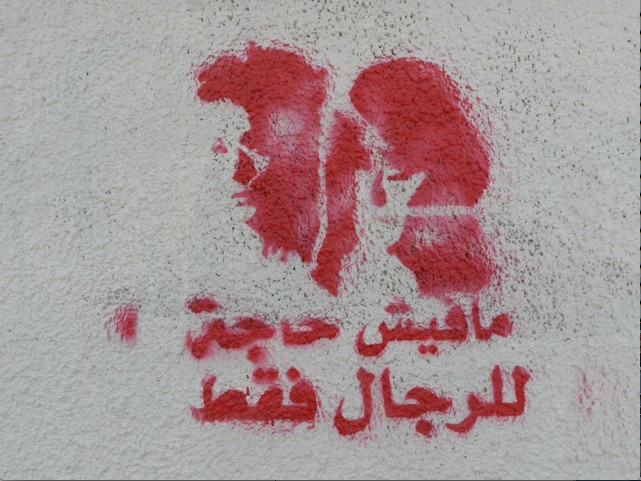

[Caption: figuring iconic actresses Nadia Lutfi and Suad Hosny “There is no such thing as ‘exclusively for men’” (Referring to the famous film Lil rigal faqat, For Men Only). Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 12 March 2012)]

[Caption: SCAF wall, Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 16 March 2013)]

How can women fail to be alarmed when the Muslim Brotherhood, as part of its community work for the marginalized and poor, as Mariz Tadros observed, sends “mobile health clinics” to Upper Egypt to offer the “service” of female circumcision? Even though the Brotherhood has denied this, researchers and activists confirm that a flyer distributed by the Brotherhood in the village of Abu Aziz in Minya did indeed advertise the service. These mobile clinics are making their rounds while the health system is in a state of collapse.

Unfinished Revolution

This article remains unfinished, much like the Egyptian revolution. It is unfinished because many in Egypt feel that Islamists hijacked their revolution with the help of the army. There is therefore no conclusion to speak of yet, while the pace at which the graffiti multiplies is exhilarating, far exceeding attempts to erase it. Since Morsi became president, the Islamists have tried to conquer the walls and produce their own graffiti, covering that of their opponents, but theirs is devoid of humor, and without effect.

Meanwhile, Egyptians nationwide have been preparing for mass protests against Mohamed Morsi on 30 June, having declared their lack of confidence in his presidency through the Tamarod (“Rebellion”) petition campaign. Egypt’s streets remain vibrant through protests and public performances, and street art is a barometer of this contestation and resistance, its visual narratives having revealed a powerful assertion of gender claims. This innovative, humorous, and thought-provoking iconography teaches us that there is no turning back. Egypt’s youth subcultures will continue to protest, and to wage their war on an ageing patriarchal regime through the lightness of being of art and laughter.

[Caption: Graffiti by Kaizer, outside the al-Ahly Club in Zamalek, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 12 September 2012)]

[Caption: Graffiti by Kaizer, outside the al-Ahly Club in Zamalek, Cairo. Photo by Mona Abaza (Captured 8 June 2012)]

[1] According to Hania Sholkamy, women represent seventeen percent in the Moroccan parliament, even after the electoral success of the religious parties, while women reached twenty-eight percent of seats in Tunisia. By contrast, Egypt scored only two percent.